Prof. dr Christophe Cognard is a full professor of Radiology at University of Toulouse, Chairman of the Department of diagnostic and therapeutic neuroradiology, Hospital Pierre-Paul Riquet. He was a guest of our Faculty, giving the lecture on thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. We had a chance to ask him several questions about interventional neuroradiology and medicine in general. Enjoy!

Medicinar: Thrombectomy is a relatively new method emerging in the field of minimally invasive neurological therapy for patients with stroke. Could you briefly tell our students what are its key concepts?

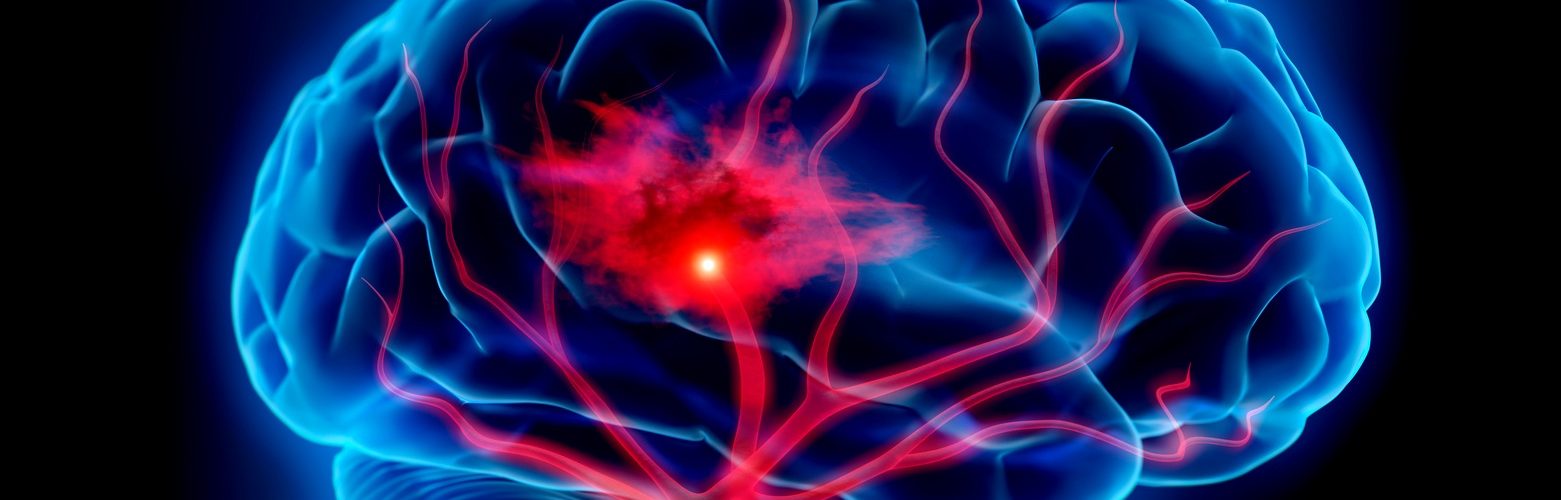

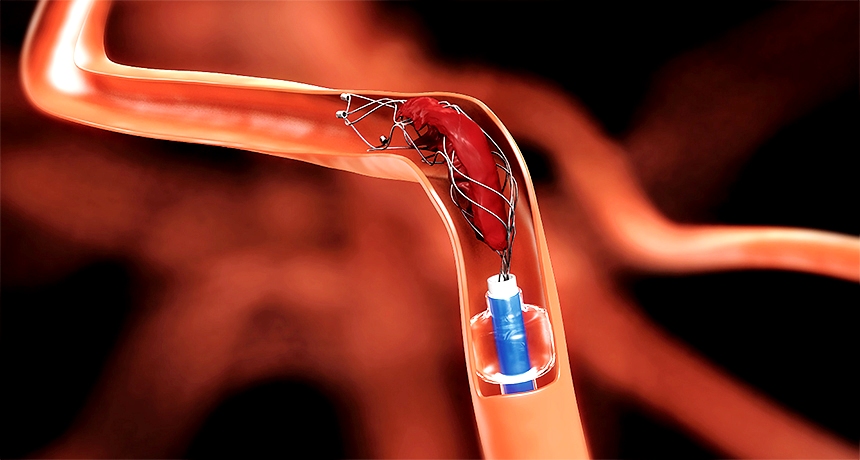

Prof. Cognard: I am what we call today, an interventional neuroradiologist. This specialty has been initially created in the ‘70s in order to treat hemorrhagic diseases of the brain such as aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations which were, at the time, difficult or impossible to treat by neurosurgery. Since then, interventional neuroradiology has developed progressively and it has become the gold standard procedure in the treatment of aneurysms and other hemorrhagic diseases. Thrombectomy is a new procedure in this field recently validated by evidence based medicine. Briefly said, during a thrombectomy, we retrieve blood clots at the time of an acute ischemic stroke. For many years this was technically impossible to do. It was not until recently that one of the big medical companies came with a stent-retriever which was designed to be used for treating aneurisms. We decided to experiment and quickly found out that this stent was highly efficient in retrieving blood clots, which was later scientifically proven by various randomized studies.

Medicinar: Stroke has various etiology and clinical presentations, so what are the indications for performing a thrombectomy on a patient?

Prof. Cognard: First you have to consider that stroke can be ischemic or hemorrhagic. Of course, retrieving blood clots is only done in patients presenting the ischemic type. Most important indication is a large vessel occlusion (LVO) in the brain, which basically means that there is a blood clot stuck in the big arteries of the brain, causing an acute tissue ischemia. This is true for about 10 to 15% of all strokes we see in our clinical practice. Usually, treatment of acute ischemic stroke includes intravenous thrombolytic therapy (TPA), but today we can perform endovascular retrieving of the blood clots.

Medicinar: Stroke therapy is time-sensitive. Today, we have general recommendations about therapeutic time window for intravenous thrombolytic therapy. Is that also true for thrombectomy?

Until recently we would never start a procedure in a patient whose symptoms were present for more than 6 hours, like it’s written in the guidelines. But since we have new studies, we know it is possible to perform an efficient thrombectomy up to 24 hours after the first symptoms have presented. This is very individual and depends on the patient. Sometimes patient has good collateral circulation and the ischemic lesion is so small that if you retrieve the blood clot, surrounding tissue will survive. On the other hand, there are cases when the procedure is not efficient even during the therapeutic time window. We must never forget that during the stroke, patients are losing about 2 million neurons per minute. So, main message is that every second counts and blood clots should be removed as fast as possible. Side note is that sometimes, thanks to the specific anatomy of the patients’ brain, we can do the procedure with a delay and still be efficient. Generally speaking, most of the patients rest in a very poor condition if the procedure hasn’t been done in the therapeutic time window.

Thrombectomy – A major advance in stroke treatment.

Medicinar: Serbia traditionally lacks enough radiologists. Could this technique be learnt and performed by a vascular surgeon or a neurosurgeon?

I think that future specialists in this field should be well trained regardless to their prior education. In France, you have to do one year of neuroscience and neuroradiology each, and then two years of interventional neuroradiology practice, so it makes a four year training in the end. For example, I was a psychiatrist before I’ve entered the field of interventional neuroradiology. Of course, majority of interventional radiologists specialized in general radiology first. Full interventional neuroradiologists are capable of performing any endovascular treatment for various brain pathologies, but it is possible to educate yourself specifically for thrombectomy. The course takes two years, and although we don’t like it, it could be useful for countries lacking enough resources.

Medicinar: What are the potential risks of this procedure? Are there any known contraindications?

Prof. Cognard: Like I have mentioned before, the major indication for thrombectomy is large vessel occlusion (VLO). In those patients, we perform thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolytic therapy together for better outcome. This has been proved efficient in different patients, no matter their age for example. When a patient has a high score on the NIHSS (National Institute of Health Stroke Scale), meaning they’ve suffered a severe stroke, it is possible to see improvement very early. Problem arises with patients suffering a mild stroke, whose NIHSS score is low. We have to measure potential benefit of the procedure compared to possible risks. Like any other endovascular procedure, potential risk of causing hemorrhage exists.

Medicinar: This type of procedure seems reserved for large hospitals and clinical centers. How do you organize a healthcare system so that distant patients get a chance for a thrombectomy?

Prof. Cognard: This is a problem all across Europe. Governments think since it’s a very effective procedure, it should be available everywhere. In medicine, things are not so simple. First, we measure cost/benefit ratio, but we also think about competence and safety. You see, thrombectomy is a difficult procedure to do – often you get called to work late at night, your patients are very old and their vessels are fragile, so even for people with my experience it can be demanding. So, if you start opening small centers everywhere you risk those doctors seeing fewer patients, which will influence their skill and competence. For example, in Toulouse we have around 250 cases per year, meaning that every day we get a chance to navigate and operate in the brain. If a smaller center has 20 to 30 cases per year, its doctors will not be good enough. Furthermore, if you’re planning to open a thrombectomy center, you have to meet many different criteria – for example, to have four working interventional neuroradiologists etc. Good organization of medical service is a complex work and we are still doing new studies about the performance of different solutions.

Medicinar: What is the future? We see different medical branches trying to lead the way in therapy of neurovascular pathologies, including neurology, radiology, vascular- and neurosurgery. Do we need a different approach to our medical curriculum?

Prof. Cognard: My opinion is that medicine should stay multidisciplinary. When a neuro patient comes, it’s good to have around a well-trained radiologist, neurologist, neurosurgeon etc. We all work together for the sake of the patient, and during our meetings we discuss and understand each other very well. As for medical school, reorganization is very complex. Today we have this approach where different disciplines are not focused on organs; take general radiology or surgery for example. I think we should be more oriented towards specific organs. Imagine for example a curriculum which includes two years of clinical neuroscience, a year of neuroradiology and then you get to choose your future career as a neurosurgeon, neuroradiologist or neurologist. I think that “common trunk” can be found for other organ systems as well, gastroenterology for example. I think it doesn’t make sense that radiologists should first learn details about prostate before specializing in neuroradiology and vice versa.

Medicinar: Serbia faces large emigration of its specialists lately, but even the French system couldn’t stay immune to current migrations in healthcare. Le Monde wrote that the number of foreign doctors working in France doubled in the last decade. What is your opinion about these migrations, are they necessarily a bad thing?

Prof. Cognard: It is the problem related to the famous numerous clausus, a government regulation which limits the number of students enrolled in medical studies each year. It is a political decision because the more physicians we train higher are the costs. That’s why we came to the position that my department has 12 senior neuroradiologists of which 6 are foreigners coming from Romania, Greece, or Czech Republic. Let me just say that I am very fond of Europe and I think migrations in healthcare are a good thing. People should be allowed to move from one country to another in search of better jobs and conditions. These migrations allow young physicians to learn different things, exchange experience and get better at their work.

University Hospital Center of Toulouse, Pierre-Paul Riquet Hospital

Medicinar: This year vaccination of children in France becomes mandatory following the measles outbreak across Europe. Why do you think we came to this point and who is to blame?

Prof. Cognard: I think that the small part of population which is against immunization, whatever that means, is influenced by many rumors and urban legends circulating. We have to know that sometimes even well-educated people are causing the problem. It’s a simple thing, if we go that way, forgotten diseases will soon come back and we will finally have a strong argument for everyone. To avoid that path, we need strong laws. But we shouldn’t over-think the problem. You cannot discuss everything with everyone, that’s why laws are for anyway. If you don’t believe me, just take a look at today’s politics all across the world.

Medicinar: What is your message to our students, what makes a good doctor?

Prof. Cognard: Well, in order to be a good doctor, first you have to like human beings. You have to like people and feel the need to take care of them. Despite all the new technology emerging in our field and emotionally separating us from the patients, I spend time every day explaining and talking to them. After all these years, I still enjoy that very much.

A.S.