Martin Dichgans, Professor of Neurology at Ludwig-Maximilians Universität (LMU, Munich, Germany) is the Founding Director of the Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research at LMU. He is Director of the Munich Stroke Center, President of the German Stroke Society (DSG), and on the Executive Committee of the European Stroke Organization (ESO). Professor Dichgans recently participated at the XI/XVII Congress of Serbian Neurologists in Belgrade. It was our great honor to ask him a few questions about medicine and science, but also what advice he would give to our students. Enjoy!

Medicinar: Could you explain to our students briefly what exactly is a small vessel disease and what is its role in brain pathology?

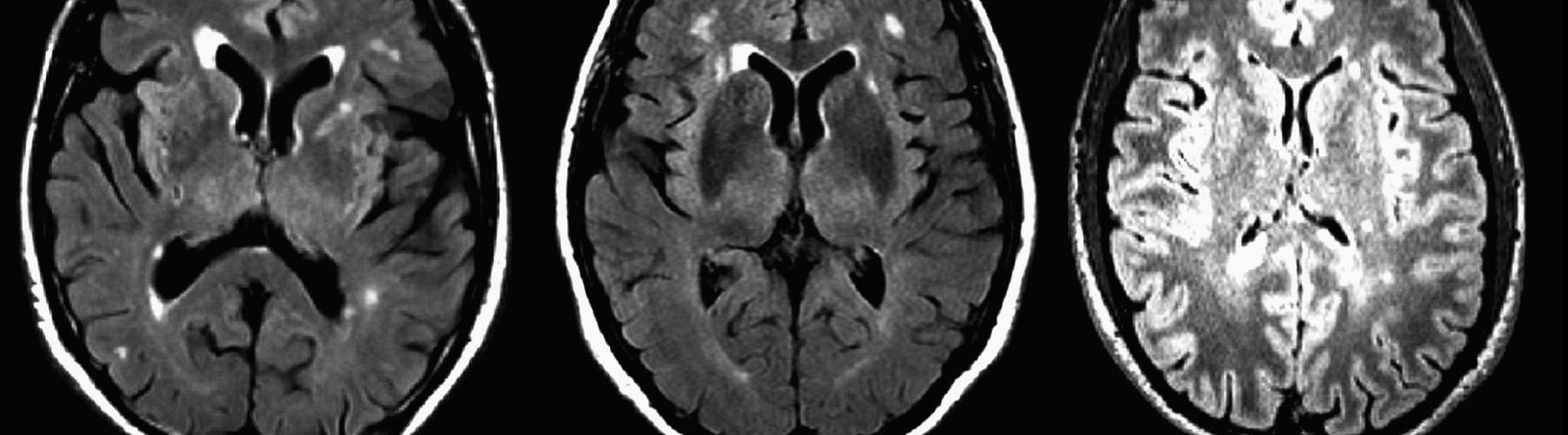

Prof. Dichgans: Small vessel disease (SVD) is one of the major causes of stroke, responsible for about 20% to 25% of all strokes. It is also the most important cause of vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), which by itself is the second most common cause of dementia, following Alzheimer’s disease. SVD is a major threat to the aging community considering that ischemic white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) visible in MRI scans or leukoaraiosis visible in CT scans are the most frequent findings in elderly individuals. Those are just some of the reasons that make SVD highly relevant for clinicians and their patients.

Medicinar: Small vessel disease is more and more in the focus of the scientists in the field of neurology. What are the major advances in its diagnosis and treatment?

Prof. Dichgans: Small vessels by definition are so small that they are very difficult to trace and track in living individuals. Despite all major advances in neuroimaging, we face limited resolution of MRI scans and other imaging modalities. A very important step forward has been made over the last few years as we identified both rare and common genetic variants that have an impact on SVD pathogenesis. Through that we have also been able to delineate a clinical spectrum of the disease quite precisely and generate mouse models that now allow us to dive deeper into the fine mechanisms of the disease.

XI/XVII Congress of Serbian Neurologists, professor Dichgans’ lecture.

Medicinar: With all the new advances of brain imaging, one could say that the basic neurological examination is becoming less important. Is that true?

Prof. Dichgans: I always say that, in the end, it is always the patient that counts. Listen to his complaints, observe the symptoms carefully and never stop with the image alone. Before all the sophisticated neuroimaging methods, the first question should always be: Are there any symptoms? If that is the case, what are the complaints that the patient has? In the case of SVD, this varies from serious stroke or TIA to cognitive impairment and gait disturbance, but also depression, slow processing speed or even apathy. Bottom line is that we don’t treat images, we treat patients.

Before all the sophisticated neuroimaging methods, the first question should always be: Are there any symptoms?

Medicinar: Serbia has a major disease burden from stroke in general population. What are the key concepts in healthcare that would improve life expectancy in those patients?

Prof. Dichgans: Well, the most relevant risk factor is hypertension. It’s also number one risk factor for all cardiovascular diseases in general. Fortunately, it is also a modifiable risk factor that can lower the incidence of dementia if managed properly. As you see, the most important things in the end are simple and we’ve known this for many years now: control risk factors, in first place hypertension.

Medicinar: What is your opinion: Is science really evolving that fast that medical doctors cannot keep up with the involvement of genetics and biophysics in scientific discoveries?

Prof. Dichgans: Well this is a challenge all over the world, especially giving the budgetary constraints and limited resources. There is an increasing divergence between physicians taking care of patients exclusively on one side and clinicians performing high quality research on the other. Scientific research itself is becoming much more complex, technically more demanding and it requires cooperation between more people with different kind of skills. These are the main reasons causing the problem.

Medicinar: Popular opinion here is that “we should leave” science to scientists and that doctors should only treat the patients.

Prof. Dichgans: That would be very dangerous. We need clinicians to be able to interpret scientific results and read clinical trials at least so they can keep up with important scientific discoveries. Otherwise we will end up prescribing wrong medications to our patients, which is already happening. There are countries in the world with very little quality control present. Of course, many factors make that situation, but one of them is medical education.

Medicinar: How would you advise our students, should they really be afraid of scientific research? Even in neurology, many scientific papers are based on studies of gene variations, are we trained to keep up with that?

Prof. Dichgans: First of all, never be afraid! Always accept the challenges, nothing is achieved easily. I was going through a lot of difficulties too, but I take them as a part of my achievement. To be honest, if you don’t experience difficulties, you are probably not on the right track. In the end, even if everything seems really complex, my opinion is that medical students are surely capable to understand, it just takes some time.

Medicinar: Coming from Germany, I have to ask you, many Balkan countries are facing mass emigration of their healthcare workers to Western Europe, while German doctors are leaving to Switzerland, Scandinavia or the USA. Is migration in healthcare a good or bad thing?

Prof. Dichgans: That’s a very good question. It is a concern, but an opportunity as well. German doctors consider their workload to be too high while their income is too low, but this is very relative: physicians coming from other countries consider those conditions satisfactory. The good thing about healthcare migration is that it can be a way to communicate better with each other, exchange experience and, in these times of globalization, secure the peace. We just need to accept that everyone has the right to move while seeking better working conditions and we should make the most of it.

Medicinar: Finally, what is your message to our students – what makes a good doctor?

Prof. Dichgans: I think the Hippocratic Oath remains the best guiding principle, meaning that you are always sitting in front of an individual and never treating a group of patients. This individual patient that you’re dealing with should always have the highest priority. Even in research, which I enjoy a lot, it is still clear to me that the patient should always come first. In order to be a good doctor and face all the challenges on your path, you should constantly try to improve and broaden your knowledge. In other words, learning is what makes you a good doctor. Intuition or what we tend to call gut feeling is often a bad advice. I mean, if you have nothing else left, go with your experience, but always be critical about it. Today’s medicine is based on evidence; it requires clinical studies and trials, especially for important questions which have no clear answers. Never consider yourself to be an excellent doctor, because, looking at the big picture, your knowledge will always be limited.

Special thanks go to ass. dr Aleksandra Pavlović who arranged our meeting with prof. Dichgans.

From left to right: Anja Stefanović (psychology student), ass. dr Aleksandra M. Pavlović (Clinic of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade), Aleksandar Stevanović (medical student), Dr Nataša Stojanovski, Nikola Zejak (medical student), Prof. dr Martin Dichgans (Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research, Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, Germany), Prof. dr Branko Malojčić (Clinical center of Zagreb, Faculty of Medicine, University of Zagreb).

A.S.